Note: Spoilers for a 46-year-old film!

I want to mark the milestone of earning my PhD by writing about the titular film for this newsletter, Hal Ashby’s 1979 film Being There starring Peter Sellers. Now that I’ve finished my education, maybe my workman-like writing is now journeyman-like enough to handle it, since the film is well-regarded and a little tough to pin down. Particularly, this film is fascinating in the way the main character, Chance, negotiates the different spaces in which he finds himself. In what follows, I’ll explore how Being There constructs meaning in four distinct spaces: the house where Chance grew up, the mean streets of Washington, D.C., the palatial estate of a billionaire, and the various media spaces that elevate him to national prominence. Chance doesn’t navigate these spaces with intent. Instead, he brings with him a kind of unreadable neutrality that each environment reshapes according to its own logic.

When I say the film is difficult to pin down, I’m specifically referring to its tonal slipperiness, which moves from satire to drama to deadpan absurdity. I’d say most of the writing about it I read online is breathlessly positive, with only some people expressing disapprobation or confusion. For example, Gene Siskel says in Sneak Previews that the film is “a poetic statement on the condition of our contemporary world,” which is high praise indeed. While I don’t necessarily agree with Siskel—I find the film too cynical to be poetic—its treatment of space is worth closer attention. In most of the films I’ve analyzed for this column, the characters respond to their environments. In Being There, it’s the opposite: Chance’s liminality reshapes every space he enters. Liminality, in this context, refers to a state of in-betweenness, or a person who doesn’t fit neatly into any clear social role or category. Chance’s liminality, which makes him neutral and unreadable, allows him to move through elite environments not with intent, but because others mistake his emptiness as depth.

In Being There, Chance is a gardener with an undefined cognitive delay who has lived his entire life inside a Washington, D.C. townhouse. He refers to his employer only as “the Old Man,” and if he’s not tending to the home’s small, walled garden, he’s compulsively watching television. The TV is his only window to the world. When the Old Man dies, Chance is turned out of the house with no ceremony or explanation. He walks into the city wearing a 1920s-style suit, carrying a leather suitcase and an umbrella, setting off to face the world with no understanding of it beyond what he’s seen on television.

The streets are the only true site of resistance for Chance. When confronted by a group of teenagers on the sidewalk, he tries to defuse the situation by pointing a remote control at them, attempting to change the channel on their behavior. It’s a darkly funny moment that reveals his slim grip on reality and how deeply television has shaped his understanding of the world. Unlike the other spaces he’ll enter, the street does not reinterpret or absorb him—it rejects him. But that rejection is short-lived. As he wanders toward Capitol Hill, he’s distracted by a storefront television display and softly collides with a limousine.

Inside is Shirley MacLaine’s Eve Rand, wife of a dying capitalist, who mistakes his quiet demeanor and formal dress for signs of refinement. She offers to take him to her husband’s private doctor, effectively lifting him out of public space and back into wealth and insulation—though this time, it's not the cloistered, decaying comfort of the townhouse, but the opulence of the Rand estate (filmed at the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, with all the warmth of a mausoleum). In this elite setting, wealth controls access and appearance.

On the way to the Rand estate, Chance-the-Gardener becomes Chauncey Gardiner after Eve mishears him, and Chance rolls with it. Ensconced comfortably at the estate, FKA Chance employs selective repetition in his conversation, repeating the last word or phrase someone says, which manages to validate the speaker and spurs them to reflect back what they want to hear from him. Eve, her dying husband Ben, his doctor, Dr. Allenby, the servants, and the President of the US describe Chauncey by turns as intense, funny, measured, balanced, intuitive, natural, sensible, and wise. The estate becomes a space of projection, not recognition; Chauncey doesn’t assert character but absorbs it, allowing those around him to project onto him the qualities they most want to see. His in-betweenness, his lack of defined role (not quite a resident, not quite a guest), makes him a kind of mirror, reflecting everyone’s desires and assumptions.

The Rand estate is his launching pad. After a media appearance on a political pundit show and an invite to a dinner for the Soviet ambassador, Chauncey incites a small chaos amongst political operatives and the press. Everyone is trying to find out information about him, but there is none. Without a dossier, he effectively has no past, which opens up his future in politics. After Ben dies, we see from the strategizing of the pallbearers at the funeral that Chauncey is the best chance to advance their interests in the future. We also see inscribed on Rand’s mausoleum the epitaph “Life is a state of mind,” reinforcing the message that perception rules in elite spaces.

Meanwhile, the man himself peels away from the ceremony and walks across the surface of a pond—a final image that leaves interpretation entirely to the viewer, just as every character has done with him throughout the film. It also solidifies his status as a liminal, or “threshold”person, suspended between categories.

In The Ritual Process (1969), anthropologist Victor Turner writes that liminal figures “elude or slip through the network of classifications” that typically organize cultural space. They are “betwixt and between,” ambiguous by design, and often portrayed as stripped of identity, rank, role, and possessions (p. 95). Chance fits this description almost uncannily. While he hasn’t undergone a ritual per se, he functions as a threshold person as he passes through elite spaces. And whereas Turner’s threshold figures are humbled to be remade, Chance is blank enough to be mistaken for what others most want to see. But unlike those figures, he is not reabsorbed into society with new purpose or clarity, only vaunted upward by the projections of others.

In fact, the only aspect of Chance that is not up for interpretation is his racial identity. He is granted the benefit of the doubt at every turn because of his race. Only two characters in the film seem to see him clearly: Louise, the housekeeper from the Old Man’s home, and (eventually) Dr. Allenby. Watching Chance’s television debut, Louise recognizes the ease with which the world accepts him: “It’s for sure a white man’s world in America,” she says, a line that cuts through the film’s surreality and names the racial privilege operating beneath it. Dr. Allenby, for his part, does the legwork to confirm what the audience already knows: there’s no there there. However, he withholds this discovery, reinforcing the structure that Louise identifies. Chance’s upward failure is one of structural power—the kind that rewards whiteness, wealth, and blankness when paired with the right suit.

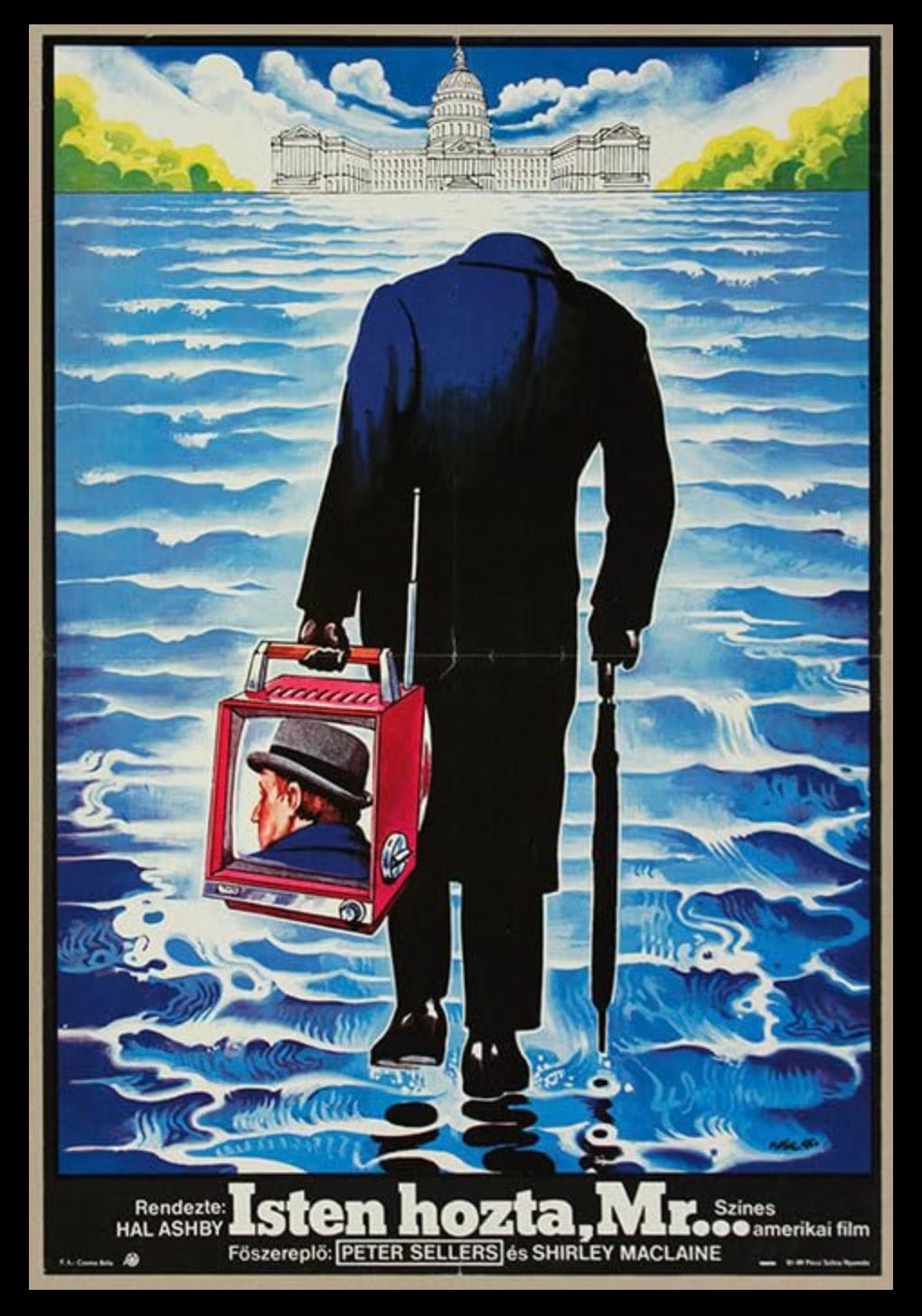

Being There remains relevant today, where power often hinges less on substance than on projection. The film critiques not just elite spaces, but the systems of perception that sustain them. And yet a loose thread in my mind is the ending. The final image of Chance walking on water seems to be read as Really Deep, Man, since it easily invites comparisons to Christ or to spiritual transcendence. But in light of the film’s deeper critiques, including Chance’s own casual racism throughout1, the image is anything but redemptive. It’s not a revelation: it’s another projection showing again how appearance can eclipse substance. Even the theatrical poster makes this dynamic literal: here, Chance is walking on air, suspended mid-stride above the Rand estate. However, it’s not transcendence. It’s just marketing, and hollow at that.

Being There Stats:

Place namedrop in the title? Nope

Filmed on location? Yup! Well, the exterior scenes, at least. Some interiors were filmed in California. Location is a state of mind!

Good, placey b-roll? Yes! The scenes to and fro the Rand estate are gold: it’s too funny that directly outside the estate’s gates we see a McDonald’s. That’s exactly where I would go after my tour of Biltmore, for sure.

Did it feel like being there? I did not feel immersed in this film on any of my watches, from the first some years ago to the rewatches I did to write this. Not sure how it would have been if I had seen it in 1979 in a theatre. I am not vain enough to think I wouldn’t have been one of these folks thinking that it is a deep film.

Real estate corner: The Old Man’s house is located at 937 M Street NW, Washington, District of Columbia and owned by a corporation like for the sake of privacy. It was appraised at $1,475,690 in 2018 and is estimated to be appraised at $1,656,910 in 2026, reflecting an increase of $181,220. This represents an appreciation of around 12.28% over eight years. And the neighborhood is no longer looking like a an area that developer would characterize as one of “urban blight.” Today it is leafy and gentrified.

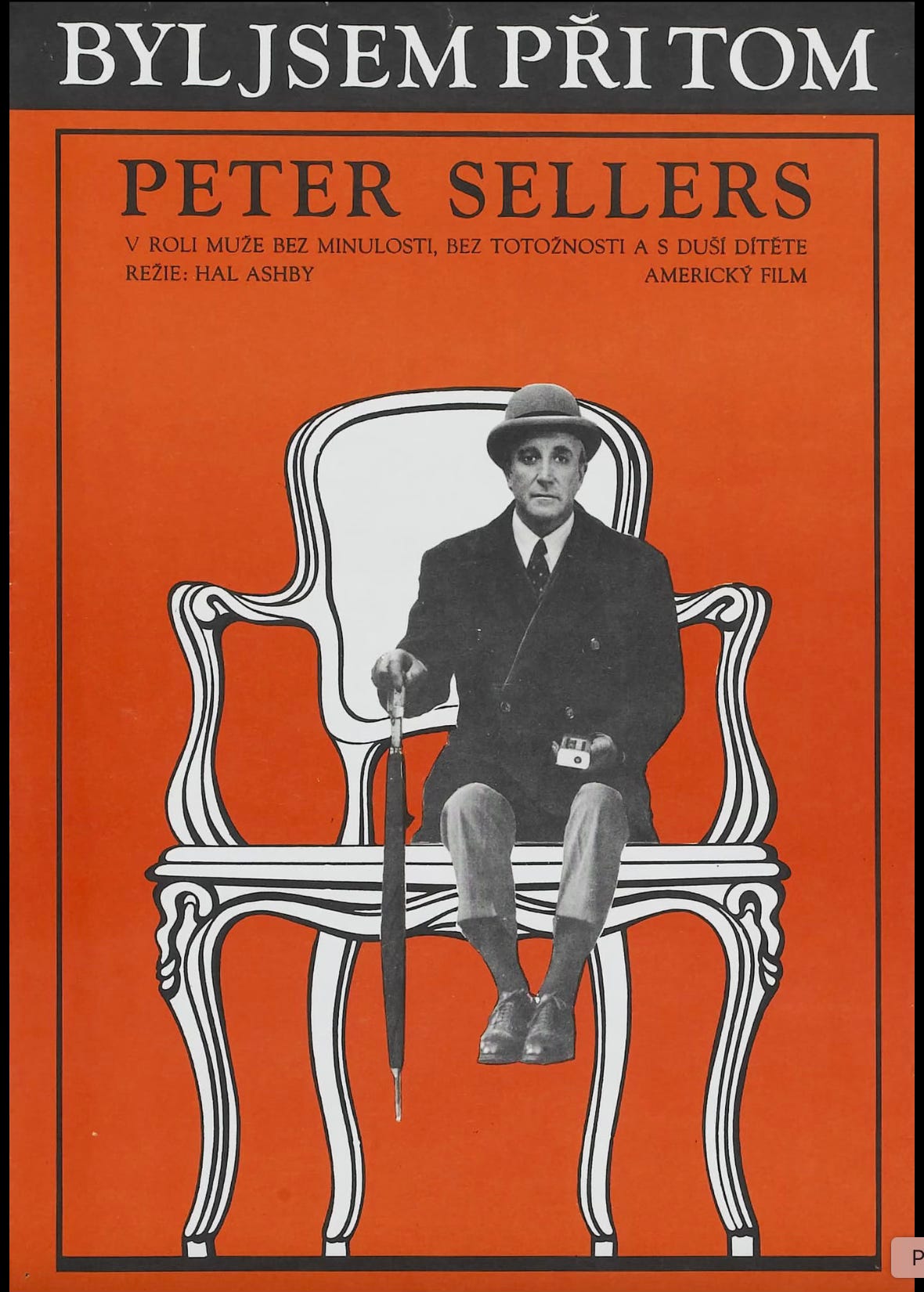

Foreign movie poster corner: Some wild film posters, Czech and Hungarian, respectively:

Namely, he thinks all the characters of color know each other or will provide food. The blooper reel in the credits extends this idea, and it’s a relief Ashby cut it, since it’s aged even more poorly.